Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Part One. The Playing Field

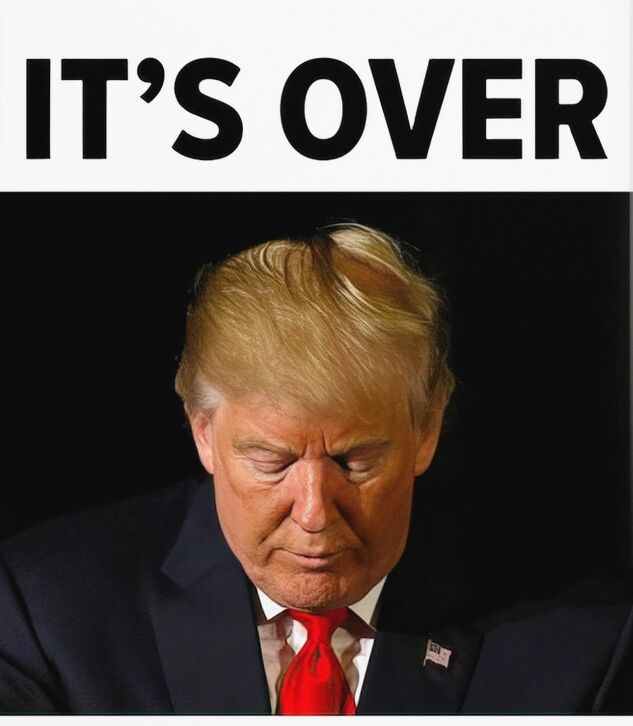

It’s over soon not because of the criminal charges, the hideous behavior, the fascism or the increasingly lunatic speeches. It’s over because of the numbers he doesn’t understand.

Four years ago I gave to my local Democratic Club a talk titled, “Why Donald Trump Will Not Win the 2020 Election.” Last month I reprised the talk, but this time it was titled, “Why Donald Trump Cannot Win the 2024 Election.” This conclusion is based not on wishful thinking or partisan ardor, but on years of experience as a political operative and consultant.

There is a great deal of misinformation, disinformation and just plain nonsense swirling around the subject of politics and elections. We must begin by clarifying where we are.

Contrary to conventional wisdom and the received wisdom of the media chattering class, we are not a nation bitterly divided, 50-50, between Democrats and Republicans. I first realized the depth and breadth of this misperception when, some years ago, I heard Bill Maher say, “You can hate Trump, but you can’t hate his supporters, they’re half the country.” Since then I have heard him and many other commentators — and many politicians — either repeat the thought out loud or assume it in their calculations. Just the the day Chris Mathews, a favorite TV anchor, said offhandedly — the way you say the glaringly obvious — that Donald Trump “has a 50-50 chance of being the next president.”

The assumption is important. If it were true, then the only way the candidate of a major party could win an election would be to convert enough members of the other party to garner more than 50% of the vote. Indeed, that is what a great many politicians spend their time and resources trying to do. That is what a great majority of people without direct experience think politics is all about — arguing with people to change their minds. But trying to convert political opponents to your cause brings to mind the old country saying that advises against trying to teach a pig to sing; it never works, and it annoys the pig.

But conversion is not what politics is about because the American electorate is not divided 50-50, not even close. In reality, there are four categories of American adults who are eligible to vote: roughly 25% are unregistered, 25% are Democrats, 25% Republicans and 25% not aligned with either major party (I use the term Independents to refer to a grab bag of splinter-party members, environmentalists, libertarians, socialists, etc., etc.) (This can be easily fact-checked at the website of the U.S. Census Bureau.)

Disregarding the unregistered, then, the electorate of the country and almost every one of its states, cities and counties is roughly one-third Republican, one-third Democrat and one-third Independent (give or take a few percentage points). There are, as always, a few outliers — Wyoming is skewed Republican, for example, Maryland Democratic. But in every single jurisdiction in which I have practiced politics over half a century, the one-third template has been close enough.

But we live in a two-party system, that in most cases winnows the actual choices on the ballot to two serious candidates, which dictates that most election results are around 50-50. Hence the persistent perception that we are a 50-50 nation when we are a 33-33-33 nation.

The implications for politics, and the way we think and talk about politics, are profound. We’ll examine them in Part Two — The Rules of the Game.