Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

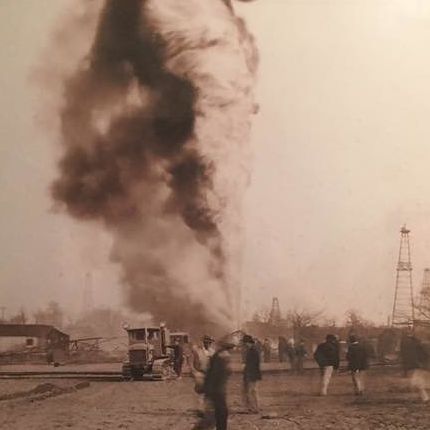

In the good old days (1929, here) a gusher like this paid you over a hundred times what you put into it. Today, not so much.

In the early part of the 20th Century, when a wildcatter struck oil, he got a return on his investment of 100 to one. For every unit of energy he used to find and bring the oil to market, he got 100 units back (money is simply a token for the energy, a marker of its value). On that EROI — energy return on energy invested — of 100:1, more than on any other single thing, rests the advent of the Industrial Age and the American Empire. When we discovered oil we won the lottery, a lump sum payment of enough cheap energy to do whatever we wanted to do, until it ran out.

It hasn’t quite run out yet, but something else almost as serious has happened. Today, when an oil company extracts shale oil from rock by fracking (hydraulic fracturing) the EROI is five to one, one twentieth of what it used to be. From a well that costs many multiples of a standard oil well to build and operate, and that will be depleted in three years instead of the traditional 20 or more. This set of facts, more than any other, explains why the Industrial Age and the American Empire are in their final throes.

But to really understand this vital equation, and the fate it ordains for us, consider corn-based ethanol, with its EROI of 1.3 to one, a gain that is only one-seventeenth a fraction of that of shale oil (if the laws of arithmetic have not been repealed, and if I grasp them at all). By federal law, ethanol makes up about ten percent of gasoline-engine fuel. It was considered an enlightened edict when it was issued because corn ethanol, made from plants, is “renewable,” unlike those nasty fossil fuels, of which no more are being made.

This would make sense if you were talking about a small, diverse farm on which you grow corn without heavy machinery, synthetic fertilizers or noxious sprays, and you distill some of it for fuel, lighting, cooking and occasional mood enhancement (as people once did on the American frontier). But what works on a small scale amid diversity never works when it has been industrialized. Never.

What the federal mandate created is a monster that scarfs up nearly 40% of all the corn grown in the United States, and spews out 16 billion gallons of ethanol a year. The growing of the corn (in endless fields of monoculture) is fossil-fuel intensive, requiring massive inputs of machine fuel, synthetic fertilizer, and pesticides. The processing of the corn is energy intensive, requiring massive amounts of natural gas. In the end the process is not sustainable, renewable, ecological or sensible, but it makes millions of dollars for polluting industries and their bloated captains. And it’s the law!

Did we say that money is merely a token for energy? If that were true, then how could these corporations be making money? Funny thing about that. One of the county’s largest producers of ethanol — Archer, Daniels Midland or ADM — has lost so much money on ethanol it has sold of some of its operations and is actively considering getting out of the business. Green Plains Inc., the country’s fourth largest ethanol producer, lost $42 million just in the first quarter of this year. With its share price down 40% this year, Green Plains skipped a dividend in June and is selling three of its ethanol plants. The entire industry, says CEO Todd Becker, is near the breaking point. According to a study by Iowa State University, the typical ethanol producer in May of 2019 lost 27 cents on every gallon produced.

This calls to mind the old retailers’ joke about the store owner who found a source of shoes for $10 a pair and planned to sell them for $8 a pair, When asked how he was going to make that work, he smiled and said, “Volume!”

Volume is good unless you’re losing money on every transaction, as is the case in the ethanol industry, the fracking industry, increasingly the natural gas industry and the oil bidness in general. They can all keep going as long as investors buy into the “American Oil Revolution” nonsense and the lenders firehose free money all over the place in defiance of reality.

But as stated in Lewis’s First Law of Economics: “If you have some stuff, and you use a bunch of it every day, one day there won’t be any stuff left.” This applies to energy and its token, money — even the highly diluted, imaginary form of money the economy is using as oxygen these days — both of which have lost the ability to perform as they once did, and are never going to get it back.

“Frisco No. 1 1929” by Michael Vance1 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

And people still think peak oil has yet to come…

Here’s the analogy I use. You live in Australia and the whole continent is yours. Only you, all by himself and the good news there is firewood to last a lifetime just laying on the ground. The bad news is it is evenly spread out across the land.

At what point do you stop using firewood as a fuel?

Same EROI problem. Even if you were able to build a Flintstone mobile run on firewood (aka fracking) there would be a limit horizon.

Yabba Dabba Do Barney!

We are getting closer to the day when we can adjust the acronym EROI to IROI – Idiocy returned on Idiocy ivested. My guess is the ratio is more like 1000:1 but it is a growth market.

Keep writing you have a deft touch!

If the EROEI of shale oil is 5:1,and of corn derived

ethanol is 1.3 :1, the EROEI of the ethanol is

about a quarter of the shale oil,not one seventeenth.

(4 x 1.3 =5.2)

Another good essay. Thanks.

Thanks for the good thought, but I don’t agree with your math, which at first glance seems exactly right. But we are comparing the return — which I take to mean the gain — for an investment of one unit of energy, which in one case is five units and another, .3 units. Five divided by .3 = 16.66666. No? If not, why not? (I have tweaked the post slightly to make it more clear I was talking about the gain)

I agree with Tom’s logic, but even so, should it not be 4 vs .3, not 5 vs .3? If .3 is the excess energy on ethanol, then 4 would be the excess energy on shale, not 5. That would make it 13:1, roughly.

Maybe. But I have a severe headache now and I’m going to bed.

Where did you find the 3 ? In one case,it is 5 units return,in the other it is 1.3.

5 divided by 1.3 = 3.84.

Also,5 divided by 3 = 1.666

Sorry. Quickly read. Still,if the return in one case

is 5,and in the other 1.3, the relevant calculation

is 5 divided by 1.3 ,I think.

Since you ask ‘why not’. The shale oil producer expends 100 barrels of oil in the various production processes,and ends up with 500 barrels of oil, giving the EROEI of 5:1.

The ethanol producer expends 100 barrels of oil in

his various production processes,and ends up with

the ethanol energy equivalent of 130 barrels of oil,giving the EROEI of 1.3:1.

Does the shale oil producer have 17 (or 13 ) times

as much oil as the ethanol producer? No. He has 3.84

times as much.

You are right about the ‘net yield’ or ‘gain’ being a more accurate representation of reality,rather than the ‘gross yield ‘numbers I used. I thought about this last night. (It’s early morning here in Australia.) So if we use the example I used above,the shale oil producer has a gain of 400 barrels,and the

ethanol producer has a gain of 30 barrels,or about one thirteenth of the shale oil producer’s gain,as Oji and The Stinging Nettle calculated.

Sorry about cluttering up the comment section.Delete

them if you want.

Delete them? It’s the most fun I’ve had all week.

Let’ s do this again: 1.3 eroi means 0.3 left to burn after spending one gallon. 5 eroi means 4 left to burn after spending one gallon. So 4 divided by 0.3 is 13.33. Cheers. Great article, as always.

No, you’re all wrong; the correct answer is eleventy-three.

Not even considered in this essay (because on one ever considers it) are the massive fossil and biofuel subsidies paid by the US government which, in part, make the whole thing appear to work. The subsidies (up to a trillion internationally) keep us from seeing the true cost of the energy we burn.

Without them, we couldn’t afford to even drive, let alone heat or cool our houses. Of course they’re also an excellent wealth transfer engine from us to the 1%. Nice job Tom, for more information on this topic, this lecture is excellent.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5WPB2u8EzL8&feature=youtu.be

The epic flooding in the Mid-West earlier this year laid waste to huge tracts of farmland – poisoned with toxic chemicals brought by the floodwaters. That farmland may not be usable for some time.

Some studies, IIRC, actually place the EROEI of corn ethanol at 1:1, effectively making it close to an energy-sink. The reason the idea caught on is our subsidized industrial agriculture makes us produce waaay too much corn, so something needed to be done with the excess so that subsidies wouldn’t be cut. Hence, the boondoggle that is corn ethanol.

All this sounds like ‘fake math’ to me!

Oh, for cryin out loud, SEE THE FIX.

Why don’t you make ethanol out of bio waste? In Finland we do that. In that way it can’t replace all the gasoline but it can be part of the solution and reduces waste.