Do the throngs in the streets of Cairo have anything to teach the passers-by in the streets of America? You bet they do. (Photo by Essam Sharaf/Flickr)

Being paranoid doesn’t mean that people aren’t out to get you. Nor does it mean that you’re ready for it when they do. We who expect the crash of the global industrial system, who believe it has already (in slow motion) begun, need to be alert for the moment when the slow irreparable lean turns into the catastrophic free fall. That is when incomplete preparations for the aftermath become exactly the same as no preparations at all. Has that moment come for us, via Egypt?

Probably not. The apparent worst-case scenario — the closing of the Suez Canal and/or interruption of the parallel pipeline — seems unlikely; they are a major source of income for the country, and the Egyptian army, which guards both, has shown no signs of being destabilized by the impending fall of Mubarak. But it seems undeniable that the fuse has burned a lot closer to the dynamite, for reasons barely touched on by the wall-to-wall “coverage” of TV personalities in Cairo.

As Egypt goes, so shall we all, for two reasons: peak oil and peak food.

Peak Oil

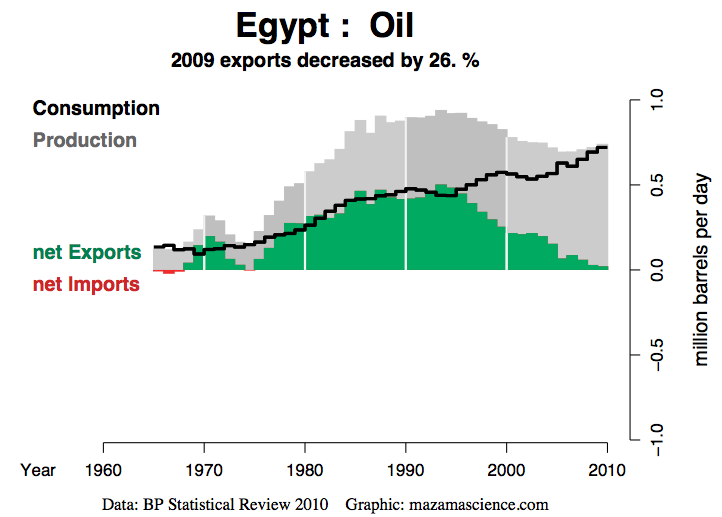

A rather confusing graph from BP shows Egypt's oil demand as a black line, oil production in grey, and exports in green.

Egypt passed peak oil in 1996, and its production has dropped by more than one-quarter since. Its oil exports have dropped to zero, and this year Egypt will become for the first time in nearly half a century, an oil importing nation. Thus it will join China, India and the US, among others, in competing for a dwindling global supply of oil that peaked in 2005, with grave consequences for all concerned in the long term.

In the short term, however, Egypt has major trouble. It used the revenues from oil exports to import food, and to subsidize the cost of food and fuel to its people. The strain had already, in 2010, ballooned its debt, at a rate of nearly $20 billion a year, to 85% of GDP. This despite the fact that the government has rolled back the subsidies, reduced welfare programs and held up needed investment in infrastructure. This year, 40% of Egyptians live on less the $2 per day — the poverty line, as defined by the UN.

This is dry tinder for the fires of revolution. What strikes the incendiary spark? Egypt has shown the way it will probably happen: the intertwined peaking of oil and food.

Peak Food

An inevitable and immediate consequence of peak oil is — peak food. In a world completely dependent on mechanized, industrial-scale agriculture and intercontinental transport of its harvests, any restriction of oil supply or increase in oil price means famine. In the 1960s (about the time it started exporting oil) Egypt grew its own food, but since then has been a major food importer. Indeed, it is a major customer for American wheat, corn, and machinery. Now, it is not the case in Egypt that fuel shortages have led directly to food shortages, as will be the case before long in other places. In Eqypt there is one more link in the chain: the decline in oil production has caused a shortage of money with which to buy (and subsidize) food. The end result is the same. People are going hungry, and hungry people will take to the streets in anger.

As revenues with which to buy food have gone down, the price of food has gone up. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization reported today that world food prices have risen for the seventh straight month — by 3.4 per cent in January — making them the highest recorded since the FAO began tracking them 20 years ago. Again, this climb is not attributable to peak oil, but to global climate change caused by the combustion of the first half of the world’s existing petroleum: floods in Canada and Australia, drought and fires in Russia, Ukraine China and Argentina, etc. But also again, the end result is the same — hungry people.

Barring dramatic and unforeseen developments (while acknowledging that all the developments in Tunisia, Yemen, Morocco and Egypt thus far have been both dramatic and unforeseen), the threads that have been pulled loose in North Africa this winter probably will not unravel the quilt of the American Empire this year. But there can be little doubt that the fuel/food fuse is burning faster, and getting shorter.

But what are the underlying trends that have sown the seeds for this perfect food storm?Biofuels are part of it clearly. And the rising oil prices that encouraged the biofuels boom are also raising food prices by making fertilizer pesticides and transport more expensive.