This view of a former mountaintop in Pike County, Kentucky, which is now lying in nearby valleys, shows what's left when the coal is gone. (Photo by iLoveMountains.org/Flickr)

In a singular act of courage and principle — the likes of which we will probably not see again while the Know-Nothings rule in Washington — the US Environmental Protection Agency last week acted decisively and dramatically to crimp the coal-mining method known as mountaintop removal. The EPA yanked the permit of an Arch Coal Company sudsidiary to devastate a mountain ridge in central southwest West Virginia.

The action was remarkable for several reasons:

- Arch Coal isn’t just any coal company, it’s the second largest in the United States. And the Spruce No. 1 Mine wasn’t just any mountaintop-removal project, it was the largest ever proposed in the history of West Virginia, perhaps of all of Appalachia.

- Mountaintop removal has for many years been Big Coal’s favorite way to get at Appalachia’s remaining wealth. True to its name, the method involves blowing the top off a mountain and bulldozing the rubble into adjoining valleys in order to get at the coal below. It’s cheap and easy, and allows the mining companies to replace hundreds of miners with huge machines, which never join unions, call in sick or require post mortems.

- As the method has buried streams and valleys, destroyed forests and tainted waters, Big Coal has donated and lobbied ferociously to protect its “right” to use this “efficient” method to get at coal, much of which it is now exporting to China. The lobbying worked. In 40 years, the EPA has vetoed exactly 11 such permits.

- The Know-Nothings who took control of the US House of Representatives this month have served ample notice on the EPA that its short-lived dreams (born with Obama’s swearing-in) of actually protecting the environment are subject not only to veto going forward, but retroactive veto, going backward.

Nevertheless, the EPA took the position in announcing its final determination on the matter that it had a responsibility to “protect water quality and safeguard the people who rely on clean water.” The project would have been business as usual for the coal fields: six miles of high quality streams buried under rubble, with countless miles of downstream waters degraded and polluted. Attorney Joan Mulhern with the public interest law firm Earthjustice, said recently that “mountaintop removal mining must be recognized as what it is, a reckless and barbaric form of mining that rips apart mountains, buries streams and waterways with hazardous waste, contaminates drinking water supplies, and poisons people and wildlife.”

Yet EPA’s interference with this “efficient” mining method brought howls of indignation from Big Coal’s wholly-owned politicians that were immediate and loud. Acting Governor Earl Ray Tomblin (who needs money to run for governor this year) organized a pro-mountaintop-removal rally at the Capitol and vowed a fight “for our way of life.” The coal industry, tone-deaf as always in the aftermath of the Arizona shootings, blessed the rally as “a call to arms.” Junior Senator Joe Manchin (who needs money to run for re-election next year) said the decision “is not just an assault on the coal industry. It’s an assault on every job market in the U.S. economy.” Senior Senator Jay Rockefeller, who doesn’t need money for anything, expressed his “outrage” because “this action not only affects this specific permit, but needlessly throws other permits into a sea of uncertainty at a time of great economic distress.” And all three of these guys are Democrats!

The pandering made many people nostalgic for the late Senator Robert C. Byrd, who never saw a pork bill or a campaign contribution he didn’t like, nevertheless never forgot whose side he was supposed to be on. Just two years ago, in what became known as his “honest broker’s” speech, he said, “the time has come to have an open and honest dialogue about coal’s future in West Virginia.” He faced openly the drawbacks of mountaintop removal and faced squarely his responsibility to represent “the opinions and the best interests of the entire Mountain State, not just those of coal operators and southern coalfield residents who may be strident supporters of mountaintop removal mining.” Who knew those were the good old days?

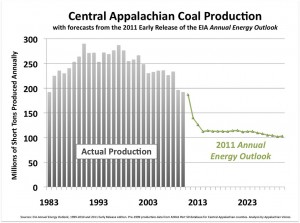

Underlying all the angst at any interference with the profits of Big Coal is an emerging, very uncomfortable fact. Central Appalachia has apparently passed Peak Coal: production has been falling since the late 1990s, and plunged by 20 per cent in the past two years alone. As with oil, getting the last of the available coal out of the ground and to market is much harder and more expensive than it was to get the first. Companies such as Arch Coal, if denied the ability to use cheap and destructive methods that will leave behind a wasteland, may well walk away from the remains of West Virginia.

Underlying all the angst at any interference with the profits of Big Coal is an emerging, very uncomfortable fact. Central Appalachia has apparently passed Peak Coal: production has been falling since the late 1990s, and plunged by 20 per cent in the past two years alone. As with oil, getting the last of the available coal out of the ground and to market is much harder and more expensive than it was to get the first. Companies such as Arch Coal, if denied the ability to use cheap and destructive methods that will leave behind a wasteland, may well walk away from the remains of West Virginia.

Chances are, however, that the wholly owned politicians will get a muzzle on the EPA, the Spruce Number One project will get its permit, and John Denver will posthumously revise his famous lyric to read: “Almost level, West Virginia…..”