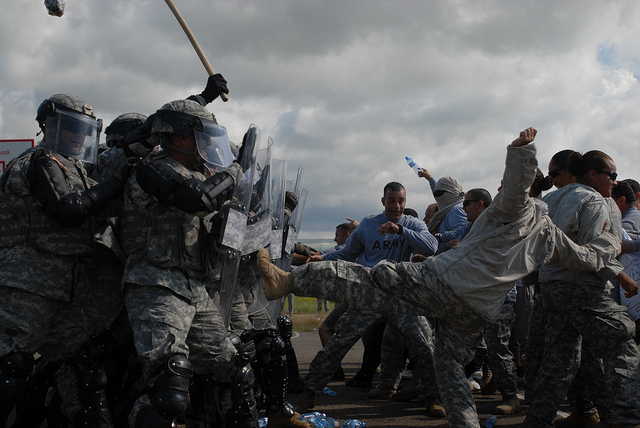

US National Guard troops train for riot control duty. Several new reports on the world's food supply indicate their services will be needed. (US Army Photo)

Crop failures and food-price shocks, often leading to food riots, are eroding world food security — which is to say they are threatening the existence of a growing number of countries — according to a number of new reports. Climate change is implicated in the most catastrophic of the crop failures this year, but scientists blame industrial agriculture for some of the gravest threats to our food supply that lie just ahead.

Among the worst of the food disasters of 2010 was the drought-related failure of the cereal-grain crops in Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan. The droughts and the accompanying historic heat wave this summer were widely associated with global climate change. The fourth largest exporter of wheat in the world last year, Russia has banned all exports this year. The sudden absence of Russian wheat from international markets has contributed to staggering increases in food costs, estimated by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization to be running between 11 and 20 per cent, with the steepest increases afflicting the countries that can least afford them.

World harvests of cereal grain this year, according to the FAO, which had been expected to post a modest gain, dropped by three per cent. Something like one billion people are suffering from serious malnutrition with no relief in sight.

This is nothing new. Despite the blandishments of the chemical-industrial-agricultural complex, agriculture has been losing ground worldwide for a decade. According to the International Food Policy Research Institute, global food prices have been rising since 2000, primarily because supplies have been falling short of demand. Institute researchers forecast that, even if conditions (such as climate, desertification, soil erosion, population increase, etc.) get no worse than they are now, food prices — and consequent hunger and starvation — will continue to rise through the 21st Century.

No one who is informed about the progression of climate change or the regression of industrial agriculture believes that things will not get worse. And a new report from the United Kingdom’s Soil Association raises the prospect of a new threat, looming in an unexpected direction. According to their study, titled A rock and a hard place: Peak phosphorus and the threat to our food security, the world is about to experience peak phosphorous, which is the “p” in “n,p,k,” or synthetic, fertilizer. The only source for commercial phosphate is phosphate rock, half of which is mined in China and the United States.

Like all other non-renewable resources, phosphate rock exists in a finite amount, which will be exhausted by massive industrial exploitation. (Perhaps foreseeing this, China has restricted and the United States has stopped all exports of phosphate rock.) The Soil Association now estimates that peak phosphate — when mine production of phosphate rock tops out and begins an irreversible decline — will occur in 2033. And, as the report points out, agriculture as we know it, which is to say industrial agriculture, simply cannot exist in the absence of industrial quantities of phosphorous. Organic and sustainable agriculture, on the other hand, will not be much affected by this particular industrial collapse.

It’s interesting to note that when Gerald Nelson, an economist with the Food Policy Institute, presented their findings to the UN climate meeting in Cancun last week, he stressed that their forecasts indicate price increases for staple foods worldwide, based on supply shortfalls, of 11 to 55 per cent during the next few decades without taking into account the effects of climate change.

In other words, industrial agriculture can wreak havoc on the world without any help from industrial polluters. But it’s going to get the help anyway.